Subsidence: a scientific word for 'oops'

The time a lake swallowed a forest, the earth ate a highway, and water dissolved salt

Let's think, friends, about some ways that mining at a specific site might end.

In some examples, mining comes to a close relatively uneventfully. Resources are extracted until they are fully depleted, or the venture is deemed no longer profitable, and the mine is decommissioned quietly.

And other times, something else happens.

Sometimes, resources are extracted up to the point at which cataclysm occurs.

This post is about that.

There are a number of ways that a mining venture can go wrong. Geologies can be destabilized; groundwater and surface lakes and rivers can be contaminated. Workers can be entrapped. The mine can flood. And, of course: everything can collapse. These risks are not multiple choice; sometimes all four of them happen at the same time. Imagine it.

Now that we've spent a few weeks considering, ahem, corporate responsibility (nods to Gulf & Western, Viacom, Kohler, Chiquita and to the ghosts of the guano companies along the U.S. east coast), I think we're ready to go back to the salt mine story. The goal, as always, is as full, and fully contextualized, an understanding of the story as possible.

And so, let's look first at what's happening these days with mining in general.

My adult home of reference is the American midwest, where on a November evening in 2011 I had a very unexpected experience: my chair shook, our chandelier shook, our house shook, and our neighborhood shook. Was that . . . ? It was. 290 miles to the south of us, Prague Oklahoma had just experienced [what was then] the largest earthquake in the state's recorded history.

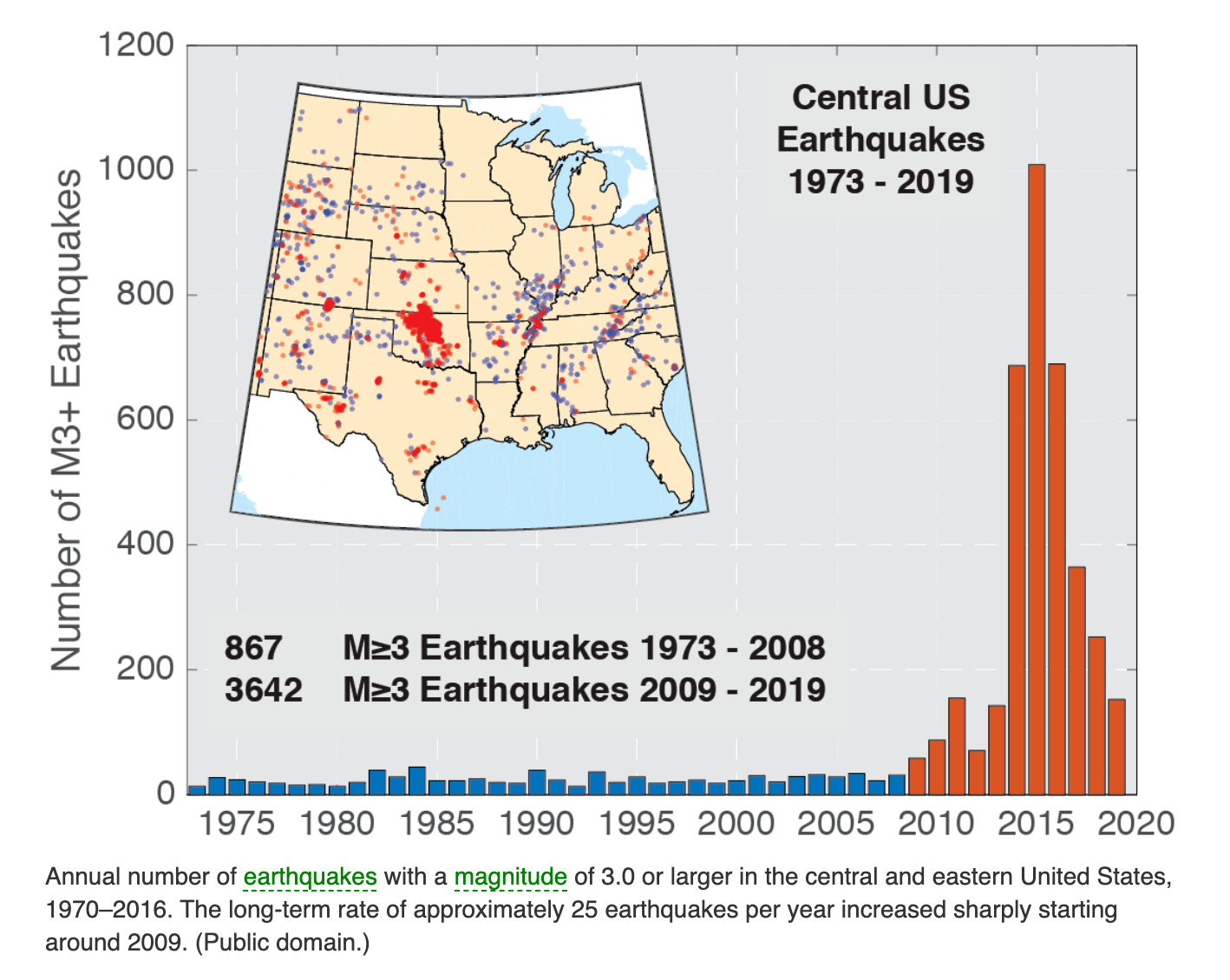

Those living in the Missouri river valley abide with a vague awareness of the New Madrid fault and its risks. Those are the source of the occasional history lesson or morbid joke, but to actually experience a temblor on the American prairie is not a likely thing. Or rather, it wasn't. Check out this fun graphic.

The USGS wants you to know (and quite earnestly, I might add) that these earthquakes are not a result of fracking. "Fracking causes earthquakes" is apparently a commonly held misconception, at least if we are talking about large earthquakes. Fracking causes small earthquakes. Larger unnatural earthquakes are, instead, the result of injecting oil-contaminated wastewater thousands of feet below the surface of the earth so that contaminants can be disposed of below ground.* In short, these larger, more destructive earthquakes are also human-caused, and also petroleum-industry related, but don't blame fracking.

Ok, got it.

Fracking, which is a word you've probably heard, is short for hydraulic fracturing, which is a term you probably haven't. The technique involves forcing water through layers of buried bedrock until the rock breaks (ie, it fractures), which means oil can more easily flow through its cracked surfaces. Fracking is messy, destructive work, and it allows for oil collection in places where drilling would not be feasible or profitable. Remember, it's always the same game, and neither fracking nor the oil industry invented it: how can we extract the resource as thoroughly and quickly as possible, while minimizing (or better yet, externalizing) our labor costs and maximizing our distribution networks? Good luck to you, American midwest.

Which brings us to the salt stories.

And to the work of Dr. Kenneth Johnson. Dr Johnson's career focused (he's retired now) on human-caused subsidence in the mining industry. Subsidence in general means 'sinking'; 'human-caused subsidence' means 'oops,' to put it mildly. Johnson served as a field specialist in both Oklahoma and Kansas, and from his work I learned the cause of something as mystifying and close to home as that earthquake that shook my living room some years ago. In our prairie years my husband and I lived outside of Kansas City, while our extended families lived in Wyoming and Colorado. We thus spent a lot of time on I-70 heading back and forth, and while road construction is indeed a time-honored part of interstate travel, there are some places that seem to see more road construction than others. Some places that seem, in fact, to never not be under construction.

I-70 through Russell County, between Salina and Hays, Kansas, is just one of those places. And it turns out that there is a reason for this, something Dr. Johnson himself studied:

The road bed is sinking. Johnson's paper on this subject is called, poetically, "Salt dissolution and subsidence or collapse caused by human activities." I appreciate a title that gets right to the heart of the matter. I will follow its lead here and explain Johnson’s findings very directly:

What's under the ground in Russell County, Kansas?

Salt, dating to the Permian era!

What else was going on in those fields?

Drilling for oil!

What happens when you cap old oil wells badly?

Water from precipitation and condensation gets in and flows downward!

And then what does that water do?

It dissolves the salt!

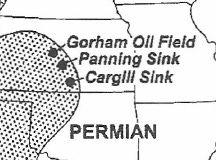

K. Johnson (2005); dotted shading is underlying salt formation; named points are incident sites

I truly do recommend this paper to you; it's quite clearly written and you wouldn’t need to geek as hard as I do about industrialism to find it both helpful and fascinating. Reading there, you’ll learn that the above is but one of many examples of what has gone wrong in the field, and in fact this is one of the less interesting tales- there's no sinkhole, flood, or spectacular collapse. But friends, the highway has to be continuously regraded near Russell BECAUSE IT SINKS 15 cm EVERY YEAR AND NO ONE KNOWS HOW TO STOP IT.

Water reliably dissolves salt, y'all . Take that one to the bank.

On which note, I bring you a story from south of the prairie, in Louisiana. A story that you will. not. believe, except that when I am finished introducing it, you are going to click on this 8 minute History Channel video and YOU WILL BE AGOG. AGOG, I TELL YOU. (Agape. Astonished. V surprised.)

Remember how I mentioned that spectacular failures in mining are not multiple choice? That sometimes, the result is "all of the above"?

The Lake Peigneur story, man. It’s got everything.

In 1981, a salt mine and an oil drilling operation inadvertently moved from coexistence to cohabitation. The cause: some incorrect trigonometry (we all need math, but some of us need it more urgently--and more accurately--than others) and a 14-inch drill bit. MERE HOURS LATER 150 FOOT TALL PECAN TREES WERE AT THE BOTTOM OF A MINE.

What was briefly, at 164 feet, the largest waterfall in the state of Louisiana. Amazingly, this had nothing to do with the mine or lake, directly—it was backflow as the Gulf of Mexico began flowing BACKWARD through a canal due to the extent of the disaster. Again: watch.

Amazingly, no one died. Three cheers for Diamond Crystal Salt safety procedures. Thumbs DOWN to Texaco.

And stay tuned for next week, when we head back to Great Lakes country and introduce a more recent spectacular failure known by the improbable name "Retsof."

j

--

*According to USGS, this contaminant-injection happens "far below" the level of aquifers or groundwater. I personally feel entirely reassured by this statement and you probably should, too.

**Did you know that you can random-email members of the scientific community to tell them how their work has been helpful to you, and to ask if they would be willing to let you utilize their drawings and figures in talking about issues? You can, and they might. Thanks, Dr. Johnson!

Hi Jordinn - I'm checking in mostly to see if I have somehow accidentally dropped off of the distribution for Rust and Reimagining. I saw a note in mid-October saying you were taking a week off and expecting to return publishing Oct. 28th, but I haven't seen anything since. To be clear, I totally believe that your ministry, family, pandemic survival, and the salvation of our country are all more important than this particular publication so it's fine if you've had to take a longer break. I just wondered if I'd missed a notice or something. And thanks for your whole-life ministry!