“Fee simple.” With these words, the legal system does magic, bringing the very earth under its purview.

Property ownership in fee simple is the unit basis of legal property rights in the United States. We will get into the history of fee simple, and more importantly, the provenance of private land ownership in general, in a future post; I promise it won’t be boring. (We’ll look at the history and subsequent bastardization—that’s right, we are going to use the language of primogeniture for our own purposes—of the Magna Carta, and if that doesn’t sound entertaining on its own, I have a truly batshit story for you involving Runnymede and Fairhaven, MA.) For now, though, just say the words: “fee simple”; if you need something linguistic to play with, consider that some etymologists think the term comes from “fief,” as in “fiefdom.”

At its most basic application, holding property in fee simple means that land is owned in perpetuity* by someone (or by a group of someones or a corporate entity), and that ownership of land comes with a bundle of rights extending down into the ground and up into the air.

Some things that a fee simple ownership allows one to do: transfer the property to someone else temporarily (examples: a lease, a life estate) or permanently (a sale, either of the property in its entirety or of some divided piece of the land or of the rights that come with the land), construct things (“improvements”) like buildings or fences on the property, dig for minerals or harvest resources.

I am flattening this a bit; what I have explained is actually called fee simple absolute; there are also various classes of fee simple conditional, which is a more limited holding- but we don’t need to get into this. There’s not only an entire legal course exploring the nuances of these property terms and the codes they invoke, but additional coursework to learn to write leases, divide condominium interests, convey property and interests therein as part of a will or trust, etc. Suffice it to say, this area of the civil law is voluminous and (dare I say intentionally) complicated, and for our purposes, just having the gist of what it means, legally speaking, to own land is enough.

And what it means to own land is very nearly whatever you want it to.

Build something? Tear it down again? Dig for gold? Drill for oil? Fish in your creek? Pour hog slop in your pond? Sell to the highest bidder? Refuse to sell, even for a bid higher than that? Buy your neighbor out, and his neighbor too, and make a golf course?

Yes to all of these and more. Go for it. This land is yours.

But wait, you say. That’s not actually true. This is the real world; there are limits.

Are there? Do you think so? [I will pause while you consider it.]

. . .

YES. This is correct; “rights” in property have always had to be balanced, and that balancing for the good of all is a key task of good governance.

Some examples of limits applied to the use, improvement, or holding of property in fee simple: the state of Colorado had to give the state of Kansas back some water; Colorado farmers own upstream property, and with it riparian water rights on that property, but the courts said they had a duty to also provide for those downstream. And in Utah, the city of Riverton got involved when one neighbor used his air rights in fee simple to build a house that blocked the sun from his neighbor’s house, and amid the ensuing dispute installed a large “art piece” of a prominently displayed middle finger facing the complaining neighbor’s home. (The news in Salt Lake during my law school years rarely lacked for comic application of laws various. Thank you SL Trib.) And sometimes hog farms get in trouble because they dump too much waste in the pond and the ponds explode; governments are taking an increasing role in regulating manure disposal. And what about the example in which the government decides it wants to build a road and forces you sell your property to them for the right of way?

In short, much of property class as taught in law schools involves learning the limits and exceptions to the otherwise unchecked rights that convey with property in fee simple. Sometimes the greater good does indeed trump private property rights, and there are a number of circumstances in which a government—a state, a municipality, a county, or the courts—have served as the designated actor and voice for that collective good.

As you can imagine, this sometimes doesn’t feel “good” to the private property owner, and these are often the examples we hear about; private citizens are discovering limits on what they are allowed to do on or with their property. Fee simple absolute exists in the real world; true absolutes usually don’t. (Thank you, hard math class! Concept confirmed.)

So, ok. But is government action under threat of force the only way that fee simple absolute can be constrained?

No. There are also all kinds of options and incentives for voluntary restraint on what you can do with your land. Some of these are about public access. Some are about maintaining land for a particular purpose- land trusts exist in most states to acquire land either for preservation from development or to return previously tilled or developed land to a recreational or wildland status. Some are about keeping land in a particular family or tribe, or establishing housing options that exclude profit-taking as an incentive.

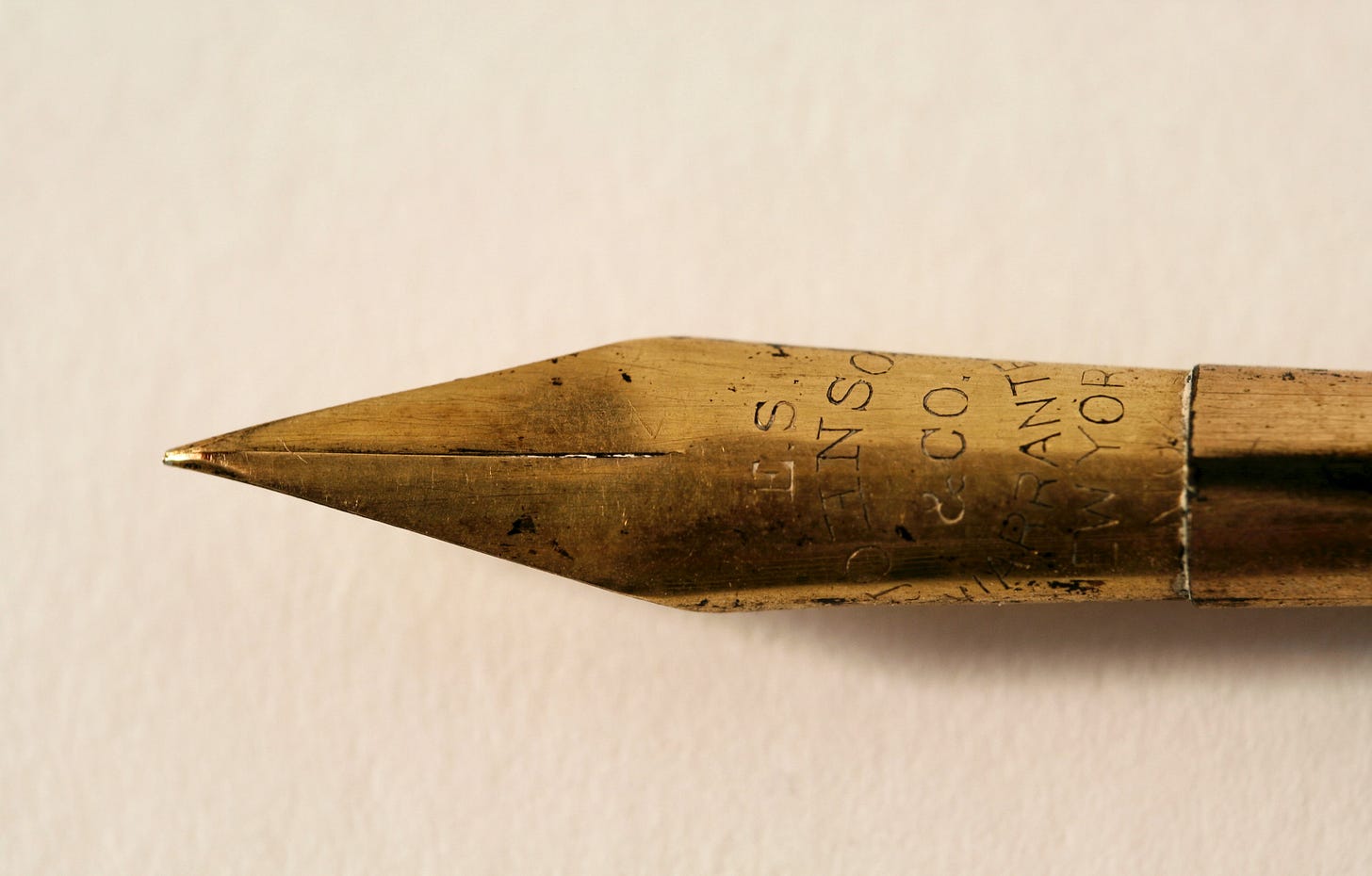

This is an extremely basic overview of voluntary limits on property rights under fee simple, and progressive faith leaders might be interested to know that choosing to self-limit under property law is usually done by covenant. We’ll return to that topic as well in a future post; like any other tool, covenanting around property rights can restore a river to health, oppress the little guy, enact and preserve racist systems, or shift the status quo. It depends who’s wielding the pen, and for what purpose.

Ok, got it. So, this all seems pretty neutral, but you keep telling us you don’t like American-style property law. What gives?

Well, for one thing, it’s primarily that I don’t like English-style property law, but we’ll talk more about that when we explore the Magna Carta. But in the particularly American context, there are definitely some things about fee simple ownership that we need to consider.

First, private property rights go so far that the public good gets considered only after there’s a problem, and enforcement action happens only after that. You can, for example, dump things in the river along your own property line for a pretty long time before anything happens to you. Further, before the Clean Water Act in 1972, there was no common-good standard or enforcement mechanism, period. And even now, when some environmental protection is considered to be in the public interest, and landholders are technically (and financially) responsible for the entire cleanup of certain chemicals, in practice someone has to notice a problem with the river, trace it back to you, file an action with the state, and then the state itself has to undertake enforcement or legal action.

At any one of these steps, the entire thing can be (and often is) dropped, and enforcement varies widely across state and even county lines. In short, if you find it profitable to dump chemicals in the river, the ball is very much in your court, and the transaction costs to stop you are steep. (Now imagine that you’re, say, also doing some campaign finance and lobbyist funding on the side, and that you focus your efforts and your charitable giving in your own community . . . it’s tricky.)

It doesn’t take much to see the practical problems with maintaining a balance here for the collective good, and the rejoinder that private property rights enthusiasts then offer is that the clearly the river itself should be private property, too—because of course it has been well-demonstrated that only clean rivers maximize profit, and that corporate ownership is deeply invested in taking a medium-to-long-term view in terms of environmental actions.

The practical balance problems are not my only concern, however. Fee simple established itself by systematically extinguishing indigenous land claims, property held in common, and any other non-fee way of regarding the world. It in effect invents itself (we’ll talk about the letters patent system soon- think of it as a “the Lord has given this land to us” printing press), and as if that isn’t sufficient audacity for one lifetime, it next declares that no one else will have rights to that property ever again except in direct lineage (inheritance or sale) with the one in whom it is vested. In other words, we are going to completely invent a claim, and then we’re going to seal the canon so that the way of inventing claims shall never be changed again. I see what you did there.

And even this isn’t the entirety of the problem; where we truly get into ontological difficulty is that in the “creation-from-nothing” myth of landholding in this country, we erase Native people not only from holding property, but from existence. This legal fiction of a blank state endures to this day, and in such improbable cases as wilderness protection. An area can only be considered a “natural” wilderness if there is no human habitation; in the Western imagination, there is development in fee simple and all that comes with it, and there is a land of trees with absolutely no one living in them.

Y’all, I like fiction. I like it a lot. Except when we’re supposed to play along with it as the basis for bolstering a system that was truly designed to be unfair.

So that, in a nutshell, is where we begin with property rights. That will be $1850.**

See you next week,

j

*This is such an interesting way for the legal system to play God. Do you even believe in perpetual endurance of matter, much less perpetual entitlement thereto by one particular occupying power? You do now.

**and also, I have a bridge to sell you.